Utopias Bach and Socially Engaged Art

Where is the art and is it any good?

Figure 1 Wanda Zyborska (2021) Dinosaur Bach no 5. postcard, pencil and watercolour.

By Wanda Zyborska

I am exploring four questions that have been tickling me, not as someone who knows the answers, but who is asking the questions.

· What is socially engaged art?

· How do you tell if it is any good (and does it matter)?

· Is there a place for formal, aesthetic criticism of socially engaged art, and of Utopias Bach as an example?

· What does socially engaged art look like (and does it matter)?

For me these four questions all arise from one. Where is the art in socially engaged art? When I ask this people sometimes assume I mean 'where are the artefacts, are there any paintings or sculptures or other traditional objects here?' But I do not mean this. I mean how can I tell when socially engaged art is being or becoming art, this conversation, group, interaction, provocation or activity, and can I apply concepts such as artistic quality to this, where the distinction between everyday life and art is blurred? Does Utopias Bach slip into and out of art? Or is it all art? Is it another form of conceptual art? Or does the apparent privileging of the participant, the removal of the hand and intention of the artist, make it something entirely different? I am a visual artist, so I also ask the question, what does socially engaged art look like?

When we come across it in webpages or galleries socially engaged art often looks something like this, a group of people doing something together:

Figure 2 Guided visualization group led by Lindsey Colbourne at the Utopias Bach Geocache Bach weekend, taking place at the TOGYG art studios as part of the Metamorffosis Festival 2021. Photo: Catrin Ellis Jones

In this experiment Lindsey Colbourne was leading a guided visualisation into imagining a better future in an embodied form that might entail a transformation into an entity of your choice, human or more than human. Elsewhere on site at The Old Goodsyard in Treborth writer Seran Dolma Utopias Bach writer in residence) was running a similar guided visualisation in Welsh.

Utopias Bach is trying to work with radial imagination to transform our futures. We feel the need for a new story. Seran described this story as the 'possibility of a turning point; powerful in its legend-like style…' The guided visualisations prompt us to think 'what if..?' Could we visit alternative communities as glimpses of the future? These small experiments in thought and imagination draw you in and it becomes extraordinary, precious, speculative and reflective; 'If you believe in magic, everything is possible' said Samina Ali.

To me these workshops manifested the substance of the Utopias Bach Geocache Bach experiment, together with a meeting we held on the Sunday and the various bilingual conversations that took place all over the site, which shared in this imaginative and experimental quality.

Figure 3 Geocache Bach conversations at TOGYG studios 2021. Photo: Lindsey Colbourne

I have been looking at various definitions of socially engaged art, including similar art forms such as socially collaborative art and relational art. In Relational Aesthetics Nicolas Bourriaud (1998) calls it 'Art as a means for creating and recreating new relations between people [and animals, plants, environment]', not showing or exhibiting art'. (I'll talk about art objects later in this blog).

Parting from the traditions of object-making, socially engaged artists have adopted a performative, process-based approach. They are 'context providers' rather than 'content providers,' in the words of British artist Peter Dunn, whose work involves the creative orchestration of collaborative encounters and conversations well beyond the institutional boundaries of the gallery or museum... 'these exchanges can catalyze surprisingly powerful transformations in the consciousness of their participants'. Grant Kester (2008).

Those of us spending time with Utopias Bach have all found it a transformative experience. We are now left with the problem of how to analyse a transformative experience, how you do compare or measure such a thing? Was our transformation big or little? How much difference did it make? Is the art the transformation? Or was the art in making the conditions for the transformation to occur? Is it this context providing process, what Lindsey refers to as 'gardening', what we should be analysing? I am going to stay with these questions rather than answer them, but it seems to me that quantitative measurements, always problematic in art evaluation, are not going to be of much use here. I will retain the idea of scale, but it will be scale as a felt experience, related to, with and from the body, and not counted in numbers.

Aesthetics in Utopias Bach

Aesthetics is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of beauty and taste, as well as the philosophy of art. The idea of aesthetics is a contested one, and one that has become associated with ideas of quality and excellence, but the word 'aesthetics' comes from aisthesis in the Greek, which means ‘bodily experience’. It doesn’t really have much to do with art per se initially. It is only in the 19th century that ‘art’ gets attached to that concept. It began 'as a way to talk about a social exchange, a way of being together, that is rooted in the individual' (Grant Kester[1]). Kester sees aesthetics as a system of transformation which could be applied to Utopias Bach visualisations. I have always been interested in how to appreciate the qualities of art, in the critical evaluation of what might be good or bad art. Utopias Bach has made me question these values, always precarious and changeable at the best of times. The Turkish artist collective Oda Projesi consider aesthetic to be “a dangerous word” that should not be brought into discussion. Claire Bishop asks if the aesthetic is dangerous, isn’t that all the more reason it should be interrogated?

To me socially engaged art is already a shifting and liminal proposition. Utopias Bach can feel like a huge challenge, to try to reimagine a better future, in an inclusive social process that is constantly being re-imagined, where the boundaries of art and life are constantly shifting and dissolving.

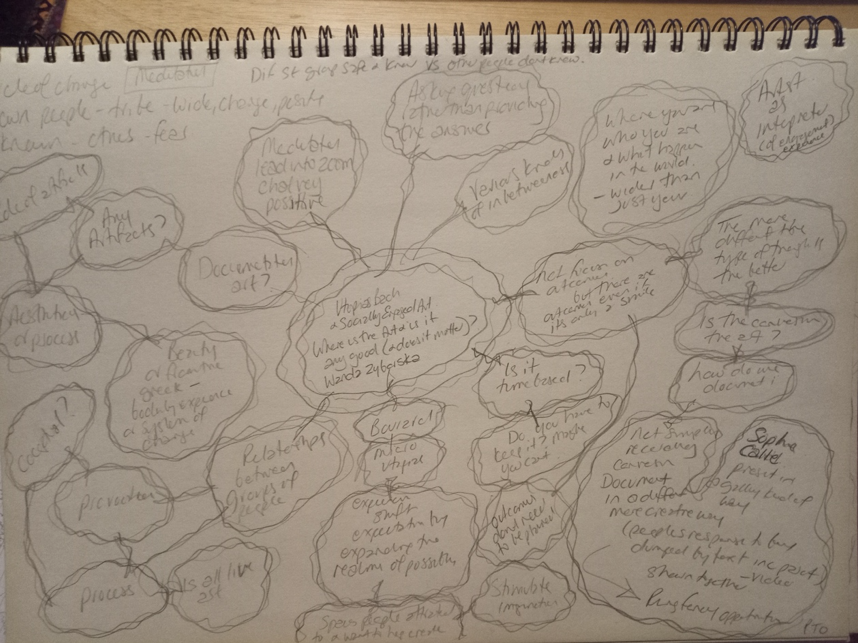

Figure 4 Gaia Redgrave (2022) map of Socially Engaged Art collaboratory meeting, or a diagrammatic expression of a thoughtful singularity.

Because of the immensity of this challenge, we decided to go small, to remove the burden of outcomes, and keep it to an experiment conducted under conditions of kindness and equality. In fact Lindsey's initial inspiration was founded in the idea of finding points of transformation in the diminutive and the local. It reminded me of Robert Morris' notes on scale written in the 1960s; 'the quality of intimacy is attached to an object in a fairly direct proportion as its size diminishes in relation to oneself[2]' where 'physical participation becomes necessary'. Although Morris was talking about sculpture I am applying his ideas to our social relations in Utopias Bach, as part of our experimentation in radical thinking. In this instance his observations support my experience of relations within Utopias Bach. There is a social intimacy in our meetings that relieves isolation and fear, and makes for playfulness and reflection.

Many people who join our zoom collaboratory meetings have been struck by how welcome they feel, and have reported how they instantly felt accepted as members of the group. Somehow we seem to achieve mutual intimacy almost immediately, in manner which is often striking (for two of our new members it was the first time they had experienced a feeling of being accepted as part of a group to which they wanted to belong). Some of us feel so disconnected and alienated by the scale of environmental problems, and the inhuman carelessness of multinational neoliberalism that we need the physical intimacy of the small in order to regain our agency. One of our new members, Gaia Redgrave, (who is currently undertaking an experimental plantlet Cathedral of Trees exploring the meaning, qualities and conditions of peace) has been so struck by the quality of our meetings that she is planning a new experiment exploring how we are managing to create the conditions for them. She wants to see if she can discover what it is that we are doing that makes people feel so instantly welcome and accepted. Called The Octopus of Omnipotence: An experiment in kindness, she defines it as;

An experiment, an embodied investigation into our ‘micro-culture’ in which we hope to better understand Utopias Bach’s welcome to neurodiverse artists and what can be learned to consciously welcome others.

Robert Morris believed that the intimacy of small objects was 'essentially closed and spaceless, compressed and exclusive'. On the contrary our meetings and relations create space, for thinking, imagining and for each other. This is supported by breaks for short meditations, for long, comfortable pauses, or just giving time for people to gather their thoughts and their confidence in order to speak. Perhaps he recognised a tendency, a polarity between intimacy and inclusion, space and confinement that we apprehended and built in structural safeguards to enable spatial fluidity.

Figure 5 Lisa Hudson (2021) A mini-utopian installation. Paper, ink, world

We are attempting to achieve similar embodied relationships with non-humans including animals, plants and even the earth and rocks in our locality, with varying success. Here the imagination becomes even more important to support our efforts.

Artists Lisa Hudson and Kar Rowson and the poet Peter Hughes are engaged in conversation with trees and rocks in specific locations in north-west Wales. In their experiment TEXTure: Asemic[3] text and communication with the non-human, they attempt to make contact with their inner indigenous. (will be explanation about indigenous and also the relation to the past in radical thinking here). In their conversations they assume the role of listener, feeling grateful and respectful to everyone in their environment. They express their insights through words, asemic writing, glyphs[4] and images. Glyph: a hieroglyphic character or symbol: In architecture: a carved groove or channel, as on a Greek frieze.

Figure 6 Lisa Hudson and Peter Hughes (2022) Conversations with an Ash

We have been using the language of aesthetics and formal art analysis on to see if it can shed light on what is happening in our conversations, relationships and meetings. Thus we might think about the texture, composition and colour of an interaction. We ask ourselves if imagination itself is an artistic medium? How do you assess the quality of personal transformation? And what is tone in this context?

In the January 2022 UB collaboratory meeting and workshop we summarised some possible critical qualities of socially engaged art, initially discussed with the last remaining student cohort of the part time BA in Fine Art in Bangor University (1998-2022). We came up with these:

• Something about the art being experienced through feelings, in the body. And in the heart.

• The energy, which can feel transformational, and authentic.

• Noticing, paying attention, awareness, and making the conditions for this.

• Reciprocity, taking from the community (people, plants, animals, land) as well as giving, listening as well as speaking.

• Taking time to build relationships, anti-efficiency.

• The quality of imagination, which should be radical and transformational.

• The constant checking of ethics, in the moment, through the body, and with others. The ethical experience must feel as authentic as possible, in the realisation that we can only do our best.

The kind of critical thinking that can take place seems more singular and personal to me than that which I employ with visual art objects, where I believe that as well as the social and personal context affecting ones response to the art, there are intrinsic qualities, shared between me and the art object, and having similar effect on all humans. Those qualities of entities always and already made under the same physical laws and properties; qualities of light, texture and composition, the cellular lines of beauty expressed under the Fibonacci sequence, the golden mean and colour principles. Perhaps the critical thinking for socially engaged art is more truly subjective, since the medium itself is a social one.

Documentation and artefacts

I mentioned at the beginning that photographs of groups of people are a way we often visually encounter socially engaged art. Photographs are an example of the varied documentary media used in recording socially engaged art. One of my first questions; what does socially engaged art look like (and does it matter) is a question that weaves its way between all my enquiries about this kind of art, and to me it often looks like documentation.

The role of documentation in art generally is another porous and shifting proposition, particularly around time based, performance and conceptual art, as well as socially engaged art. Is the documentation part of the art or even the art itself? In that case who is the artist? The one being documented or the one taking the photograph?

For many performances the photographs and associated texts will be the only way we can encounter the art. In the commercial art world they are often treated as the art itself in the sense of art as commodity. Marina Abramovic for example sells a limited number of prints of a limited number of photographs of her performances for a high price, the originals are deleted.

But what of photographs of anti-commodification socially engaged art such as Utopias Bach? Could they be asemic symbols or glyphs, without meaning in themselves, but providing us with the intuitive prompt that might enable us to imagine an experience of the original work? Whatever we decide they are, that would not necessarily protect them from commodification if the commercial art world decided there was some value in it for them.

Figure 7 Elis Jones (2021) Utopic Installation Bach, Geocach Bach, Metamorffosus, TOGYG studios, Treborth. Photograph Lindsey Colbourne

And what is the role of any artefacts that might get made during the project? Are they just a pretext for the conversations that take place and the relationships formed? To me they may be a pretext as well, but they are still art objects just as much as any others, and as such may be admired or criticised, and express their own meaning, affect, and encounter. However in Utopias Bach there is no pressure for any art objects to be of any particular quality, no selection or judgement. It is hoped this will free people from inhibition and help with imaginative expression. This is a place that many artists try to enter when making, outside of judgement, which comes later.

The pretext itself itself is important. There is a zone one can enter in making that releases creativity and imagination, and encourages a feeling of warmth and connection between the participants. Quilting circles are an example. Some of us are primarily visual artists, and find ourselves inserting and threading the visual throughout Utopias Bach, in a viral assertion of what we can see, and its importance in all our activities.

Figure 8 screen shot of moment in Collaboratory meeting March 23 2022

I have been fascinated by the aesthetics of Zoom since I entered it for the first time in the first Covid lockdown. The Mondrian-like rectangular divisions, each a separate moving portrait. Watching myself at the same time as talking to others. How much we can see of each body (head only? torso? top of head?), and the varied, usually domestic, backgrounds, including occasional pets, children and other family members. I began performing inside my border, making shapes and breaking up the edges with my arms, moving or being still, trying to get my legs into the frame. Others joined in. When someone was sad we all spread our arms and tried to make visual a group hug.

At the end of a meeting when there were only three of us left on screen, we decided to make exquisite corpses, working out how we could line up the screens one above the other to make the three separate spaces that equate to the folded paper:

Figure 9 Sarah Pogoda, Wanda Zyborska and Lisa Hudson (2022) Zoom Exquisite Corpse. Photo: Sarah Pogoda

We have made a few of these now. The exquisite corpse is a Surrealist visual tool that we frequently utilise to try and free our imaginations. Another visual intervention is using the various video filters on Zoom, as Sarah Pogoda is doing in the top frame of the exquisite corpse in figure 9. Her more usual choice was a mouse, and various backgrounds that can overlap the individuals body and margins are another medium for visual play.

Figure 10 Utopias Bach Exquisite Corpse by the Utopias Bach Collaboratory, November 2021

Art objects and socially engaged art - where is the visual?

Another artistic appropriation has been the agenda, and other administrative tools. We make up new names for them, and draw them

Figure 11: Collaboratory agenda by Wanda Zyborska

I think our Utopias Bach polarities (polarities are one of our tools of radical thinking) are coming into effect here. A polarity between relational process and art object, and another between visual and verbal expression. I am living some porous contradictions here that I am trying to negotiate. I am a visual artist fairly obsessed with art objects, their qualities and affect. I have spent years developing ways of thinking visually, trying to escape from what I see as the restrictions of language, a largely patriarchal structure in my culture. But it is not just the visual, it is the tactile. It is thinking through the skin, and with the hand, eyes, ears and tongue, as an embodied creature. This has always been my primary purpose, and I must inject it into everything I do.

So what I am thinking is that this is another polarity, where the visual and the social (to me) feed each other and overlap, something like the art-life polarity, porous and interdependent. As far as critical analysis goes, it seems to me that we might need two systems, one to look at the qualities of socially engaged art mentioned above, where we are looking at the nature of the conversation and the relationships, the imaginative energy that is created by these interactions. The second is the more traditional analysis of the visual art that may be part of it, such as objects created in a workshop that might be primarily concerned with building new relations with a community. The visual aspects could be analysed in terms of form and content as always, but again I imagine overlaps and interactions between these two areas of analysis.

In Relational Aesthetics (1998)[5], Nicolas Bourriaud suggests a network of micro-utopian projects to replace the single, monolithic utopias from classical utopianism. As a method for participation, micro-utopias create experiences that shift expectations by expanding the ‘realm of the possible’. the idea is "you never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete." micro-utopias have manifested as small-scale ‘do-it-ourselves’ temporary community centers, micro-libraries, free schools [and universities], food gardens, free stores, or digital platforms for collaborative political decision-making. The purpose of micro-utopias is to stimulate public imagination by creating experiences in everyday life that bring an ethic of generosity, enjoyment and community. If well constructed, micro-utopias are spaces that people are attracted to, places that people want to visit, to live within, and to help create.

This mixed panorama of socially collaborative work arguably forms what avant-garde we have today: artists using social situations to produce dematerialized, antimarket, politically engaged projects that carry on the modernist call to blur art and life. Claire Bishop[6] (2008)

The urgency of this political task has led to a situation in which ALL such collaborative practices are automatically perceived to be equally important artistic gestures of resistance: There can be no failed, unsuccessful, unresolved, or boring works of collaborative art because all are equally essential to the task of strengthening the social bond.

Claire Bishop argues that it is also crucial to discuss, analyze, and compare such work critically as art. How do you find artistic criteria by which to judge social practices especially when there is a standoff between the nonbelievers (aesthetes who reject this work as marginal, misguided, and lacking artistic interest of any kind) and the believers (activists who reject aesthetic questions as representing cultural hierarchy and the art market)?

The social turn in contemporary art has prompted an ethical turn in art criticism. This is manifest by paying attention to how a given collaboration is undertaken. In other words, artists are increasingly judged by their working process—the degree to which they supply good or bad models of collaboration—and criticized for any hint of potential exploitation that fails to “fully” represent their subjects, as if such a thing were possible.

So ethical and political criteria are used to judge the work, but how does this work? Is it about changing minds? Making people better? Happier? We can all imagine...

[1] http://www.publicart.usf.edu/CAM/exhibitions/2008_8_Torolab/Readings/Conversation_PiecesGKester.pdf p1.

[2] Robert Morris (1966-7) Notes on Sculpture 1-3. P817 in Art in Theory 1900-1990, Harrison and Wood (1992) Oxford: Blackwell

[3] Asemic: using lines and symbols that look like writing, but do not have any meaning. The reader can use their own intuition to imagine a meaning.

[4] Glyph: a hieroglyphic character or symbol: In architecture: a carved groove or channel, as on a Greek frieze.

[5] Nicolas Bourriaud’s Relational Aesthetics: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N_UOa2MS2Dw (1998)

[6] Claire Bishop (2006) The Social Turn: Collaboration and its discontents. https://www.artforum.com/print/200602/the-social-turn-collaboration-and-its-discontents-10274 Accessed 1 Dec 2021 Print February 2006

Further links/watching/reading:

“Manual for Social Change” a short blog by Lindsey Colbourne about Suzanne Lacy and Socially engaged art

Watch Wanda’s Collaboratory on Utopias Bach and Socially Engaged Art:

Part 1:

Part 2